Words have wielded immense power since time immemorial—to communicate, to convince, to spread ideas, to change minds, or even to create new ideologies. We are all aware of the profound influence that holy books have in various religions.

When I first learned to read, I was at a time in my life when I needed to escape from where I was. With a flip of a book cover, I could escape into the snowy Alps with Heidi, or explore the magical land above the magic faraway tree, or float along with James and his friends atop a giant peach.

I am not the only one who escaped into the world of books when I was young; they have long been a refuge for others. Many protagonists I’ve read do the same, and in those moments, I felt connected to them—like Matilda, in the book of the same name by Roald Dahl.

Although I didn’t teach myself to read or walk to the library in secret like Matilda, I did something similar. After learning to read in Kindergarten (bless the teachers), I pestered my mother to take me there, usually on weekends when she had a bit of time off from her full-time job.

It’s only a 5-minute drive—pass the Chinese cemetery, and then through stooping raintrees over quiet roads along glistening lakes—to the Lake Garden, where the library is located.

If I had not been scared so much about never walking out of the house alone—more scared of the living than the dead—I might have walked there daily, just like Matilda.

I recall my first time entering the library —a neoclassical colonial bungalow built in 1880.

The building stood tall as I approached, with columns supporting a high-ceilinged verandah featuring arched openings. The wide eaves and elevated structure allowed natural airflow, offering relief from the tropical heat.

Pushing through the large, heavy wooden door felt like entering a secret place. Inside, always cool and calm, with ceilings as high as the sky, and space as wide as the fields, it was a sanctuary.

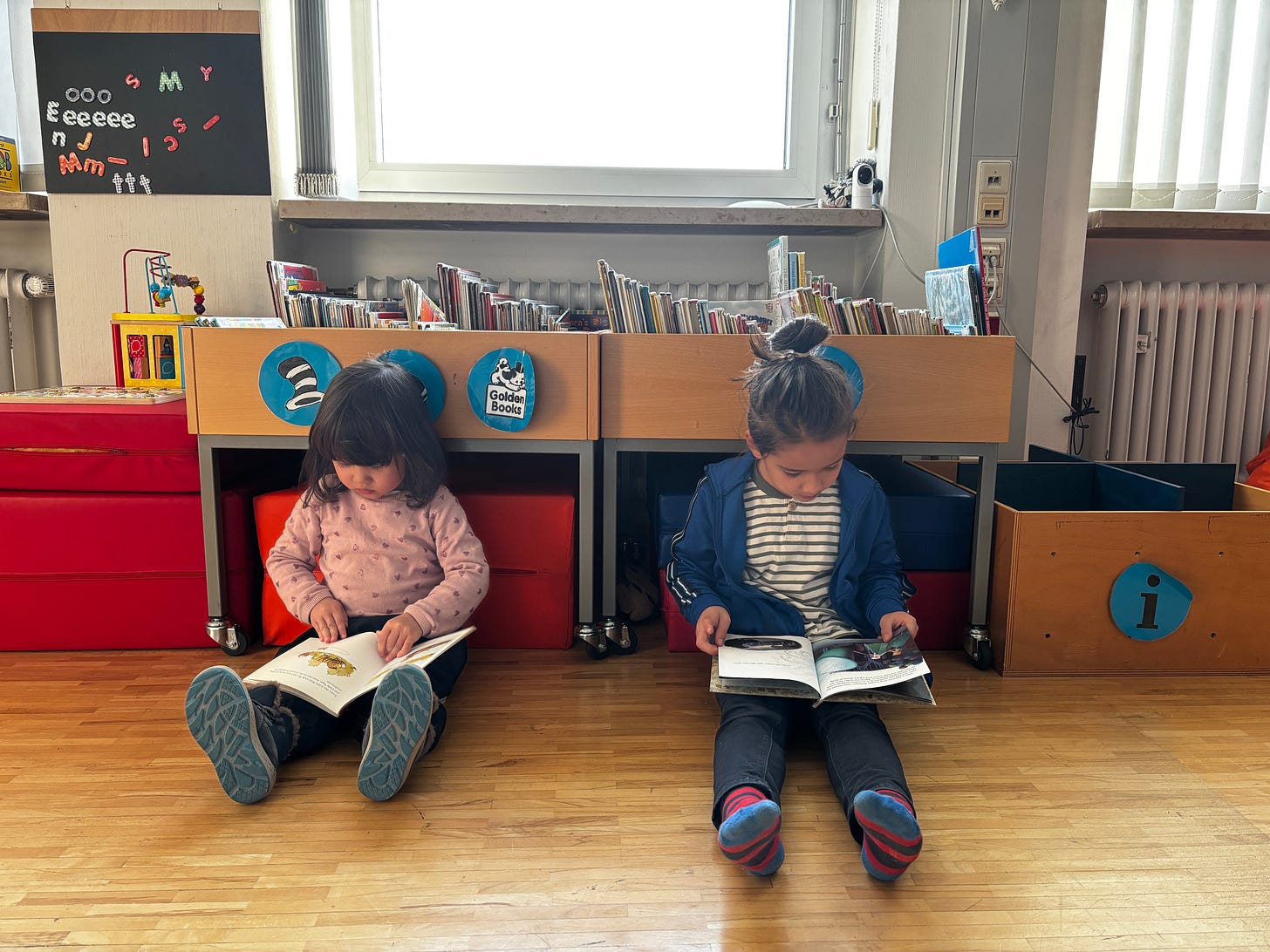

The librarian greeted me from behind a formidable desk; she held the power to choose which magic I could take with me home. Initially, she ushered me to the young children's section, where the shelves were lower and a carpet invited us to sit and read.

But once I had exhausted the books from that area—particularly all the Enid Blyton books—I ventured out and traversed the rows and rows of books, giddy with the prospect of discovering a treasure.

As I roamed, I noticed a slim, green-covered book at the end of one of the endless bookshelves, its edges tattered and worn, the pages brown. It was The Lord of the Flies, and I don’t remember what compelled me to borrow it. Nobody questioned if I was old enough for it, and it haunted me long after I had read it.

It was undoubtedly a masterful work. Its words held power beyond my young understanding, and they altered who I was forever. Its effect still reverberates in my mind.

And that is the magic of words. The magic of literature. And that is why I write.

I write to make magic. To change minds. To communicate. To connect.

I write to connect with my innermost self, to allow the subconscious to speak and the conscious to listen. Some beliefs may no longer serve us—outdated views, assumed truths, inherited patterns. Writing lays bare the soul, reveals the mind’s workings, and rewrites the deep operating system of the self. A kind of mental defragmentation. A reconstruction of the beliefs that shape us.

I write because I must. My mind has filled with words, rising like mountains ever since I learned to read. If I don’t let them out, they’ll erupt like a volcano, laying destruction in their wake. Writing opens up space within the mountain, letting words flow like waterfalls, sometimes gushing, sometimes trickling, constantly flowing into a glistening lake, then onward through rivers of consciousness, into the ocean of the universe.

This is why I write

I write for the ancestors, long gone—a belated letter of sorts. Somehow, somewhere, they would receive it, in ways we cannot perceive. There is still so much we do not know about this world, this universe.

I write for my parents, dead and alive, even if they would not or could not read it. And even if they do, they might not understand, but I write for them anyway.

I write for my children, so they would know who their mother is, and where they ultimately come from and are shaped by.

I write for you so that something in my words might resonate with you. Although only we can truly know ourselves, I hope we feel a little less alone and a little more understood.

It’s an invitation. The writer is saying to the reader, “Come along with me while I tell you a few things and explore a few ideas.” The writer is saying, “Come a little closer and I’ll confide in you about a few things.”

The hope is those confidences will inspire the reader to unearth some of his own feelings or insights. - Meghan Daum, via The Marginalian

I also write to myself. To the girl I was, so she sees how far she’s come. To the woman I will become, so she remembers where she came from.

This is why I write.

Storytelling, as Ursula Le Guin reminds us, is how we find our place in the world.

Storytelling is a tool for knowing who we are and what we want, too. If we never find our experience described in poetry or stories, we assume that our experience is insignificant

And so we keep on writing, paying attention, observing, contemplating, and making sense of things, and communicating them to others.

This is how we tell stories of ourselves, create memories, and sometimes, make a difference in someone else's life.

We write to feel less lonely, more significant. We write to be present in the world, with others, and with ourselves. We write to live more consciously.

If you want to experience more of the magic of literature—to connect, to feel a little less alone, and a little more understood—consider